Falling Off the Horse

While Leading with Liberating Structures (LS) by Keith McCandless

Overcoming bad habits is hard to do. It helps to have a gratifying substitute for a bad habit. For me, Liberating Structures (LS) are helping me become a better leader. LS introduce tiny shifts in way we meet, plan, decide, and relate to one another. They put the innovative power once reserved for experts only in the hands of everyone. By design, LS distribute control and unleash all voices so that participants can shape direction as the action unfolds.

Below, I detail my struggle with stopping unproductive behavior and share a few tips for "getting back on the horse."

1. Talking Too Much

2. Making Vague, Aimless, or Irrelevant Invitations

3. Setting the Bar Too Low: Accepting Whatever Happens

4. Moving Forward Without First Looking Back

5. Neglecting Imaginative New Uses

6. Facilitating Timidly

7. Settling for Inadequate Space

1) Talking Too Much

My most common mistake is to talk too much about the origin of or theory behind the LS microstructures. I assume that participants care as much as I do. Also, I talk more when a little nervous. ;^)

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: state the purpose of the activity in 1 minute or less and then jump into what you are inviting participants to do

- I often paraphrase the LS one liner (e.g., 9 Whys: Make the purpose of your work together clear)

- One option is to share an example of a very sharp result (for 9 Whys, here is a powerful purpose that is a collective expression of personal purposes… the United Religions Initiative exists to stop all religious sponsored violence everywhere in the world)

- Do whatever it takes to calm yourself before starting (e.g., breathe deeply)

- Substitute a question and curiosity for a statement or the advice you are tempted to give

With Liberating Structures the focus is squarely on user experience and self-discovery among group members—not the facilitator’s expertise or experience. A minimalist, less-is-more bold approach to leadership is helpful.

2) Making Vague, Aimless, or Irrelevant Invitations

My second most common mistake is to offer a fuzzy conceptual invitation—not linked to a tangible activity, the participant’s local reality, or a practical purpose. Without clarity, over-explaining makes a vague or irrelevant invitation even worse.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: launch the activity with very clear structure

- State the invitation (e.g., you are invited to interview one other person about what they do when working on ____, and why what they do is important to them);

- Specify how space and materials are used (e.g., face-to-face, knee-to-knee, jot down key phrases that sum up your fundamental purpose)

- Specify how participation is distributed (everyone has an opportunity to contribute!)

- Specify group configurations (2-4-All) and then remind them as needed

- Specify timing (10 minutes to total, 5 minutes for each interview)

- If working in large groups, project a PPT slide with this information

- It helps to signal that the launch description is complete with, “Is it clear what I am inviting you to do? If yes, go wild!”

- Expect that some people will want more clarity—clarity that can only come from them engaging in the activity. Sifting, sorting and making sense of alternatives is work for group members to complete—not the facilitator/leader.

- Invitations should be loving, provocative, and ambiguous in a way that each person brings their own meaning to the party.

On purpose, you are precisely ambiguous and intentionally a minimalist as you launch Liberating Structures. Clarity emerges out of their interaction. Help them notice when it happens… and then take it up a notch!

3) Setting the Bar Too Low, Accepting “Whatever” Happens

My third most common mistake is NOT checking in, clarifying, and asking for more tangible examples as the experience unfolds. I can be too timid in asking for more rigor and clarity. I do not always apply enough encouragement & loving provocation for everyone to perform at a high level. Often, the group knows they need to dig deeper for better solutions. It is my job to remind them they are capable of much more.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: Jump in to help participants make progress as the experience unfolds

- Part way through, use bells to interrupt and check in with participants by getting a handful of quick reports from group members—rapid fire is effective

- Ask for one example of something interesting, surprising or illuminating that is coming out of their conversation. What stands out? So what? Is there a pattern?

- If you are not a member of the group, ask for help clarifying next steps. Rely on people in the group to help you notice what is novel, a source of productive disagreement, or a springboard for action and discovery.

- Amplify or affirm tangible insights and successes; briefly try to redirect people than have missed the point (it is easier to affirm success than fix)

- Be comfortable with differentiating the quality of insights. Brilliant contributions will bounce around the room from group to group. No one person or group will drive all the action.

- Be sure to record top insights and actions in your proceedings. Make them visible on wall "tapestries." Their contribution to making progress may not be immediately apparent.

- Ask, “Have we plumbed all the depths and explored all the peaks?” “Do we need to dig deeper or come back to this topic?”

With quick reports from a few small groups, the participants urge each other on and shape next steps very rapidly. You play with and pounce on the insights and actions taking shape.

4) Moving Forward Without First Looking Back

My fourth most common mistake is NOT taking time to debrief what just happened… or what happened well before the current interaction.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: Make time for short debriefs as you go

- Ask repeatedly, “What did you notice about the experience?” Or, "In addressing this topic, what lingers from all the experience we have shared prior to this gathtering?"

- You can suggest a 1-4-All or simply invite a few comments

- Make note of what is produced and how to harvest the results in shaping next steps

- Start with comments about the experience of using LS and then migrate to what new content or novel ideas popped up

- Invite people to notice microstructure design elements: invitation structured, participation distributed, groups configured, space arranged, & time scheduled.

Ask, “What did the structure make possible? How is this structure different than what you normally do?”

5) Neglecting Imaginative New Uses

My fifth big mistake is not taking time to imagine and then share diverse application ideas immediately following the debrief.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: Make time, after the debrief of the experience, for application ideas and stories

- You can suggest a 1-All or simply invite a few comments; one or two minutes to think quietly is very productive

- You can invite people to think of applications @ smaller and bigger scales

- Ask, "What seems possible now?" and "What are the adjacent possibilities? What novel ideas are hovering on the edges of the present state of things?"

- You can share examples from your experience

- Invite others with experience to share via brief stories

Ask, “What other settings and for what challenges can you imagine using this Liberating Structure? What seems possible now?”

6) Facilitating Timidly

My sixth common mistake is timidity. It happens when I do not honor the microstructure design elements (e.g., not keeping the experience moving with rapid cycling). It can feel clumsy or a little rude to interrupt people, adjust configurations (e.g., pairs not threesomes), or move forward before everyone feels comfortable.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: Be bold! Believe before you see results. Be confident that productive and better-than-expected endpoints will be generated!

- Follow the simple rules or Min Specs of each LS… then you can break them

- Review carefully the Min Specs before you start

- Let folks know ahead of time that you will be interrupting people and making quick changes in configurations in order to co-create the best experience

- Follow the time limits with an audible and visible timer (you can project a countdown clock on a screen)

- Acknowledge that all voices will not be heard in any given debrief

- Invite participants to gather all fabulous ideas/suggestions/actions on post-it notes to be added to “wall charts” (e.g., for TRIZ a stop doing chart)

- Remind everybody that the magic happens as insights and action emerge out of their interactions, not from the efforts of the facilitator or a single leader

- If a LS is going off the rails, stop and restart from the beginning

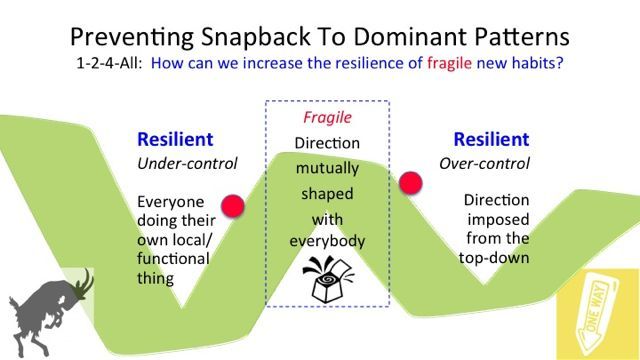

Follow the simple rules or Min Specs of each LS. Try to recognize that new habits sparked by LS are fragile while over- and under-controlling habits are well established. Repetition is a source of innovation. Walk in the shoes of others when old behaviors snapback. Relapse happens! Mastery comes from experience—success + falling off the horse in fits and starts.

7) Settling for Inadequate Space

My seventh mistake is settling for a location or meeting space that is not suited to high engagement, frequent movement, and messy co-creation. Massive immovable tables, cluttered walls, poor acoustics, and chairs bolted to the floor stifle co-creation.

GETTING BACK IN THE SADDLE: Make my needs explicit, fight hard for getting the most flexible space even when it is uncomfortable, get there early to fix problems

- Send room layout and AV needs well in advance of an event or meeting

- Ask for photos, sound checks and diagrams to confirm what is available

Send photos and examples of successful layouts and equipment in advance

- Everyone needs to hear and see everything that happens—more microphones, multiple projections screens, and rolls of “tapestry” paper for long wall charts can really help with large groups

- Arrive at venues with enough extra time to fix problems

Say, “We will change configurations multiple times during our meeting. We need open wall space, extra room to move chairs around, adjacent areas for informal social interaction, and top notch sound & projection systems.”

Try to recognize that new habits sparked by LS are fragile while over- and under-controlling habits are well established. Be kind to yourself. Walk in the shoes of others when old behaviors snapback. Relapse happens! Simultaneously and mutually shaping direction with everybody is a new set of behaviors! Mastery comes from experience--success + falling off the horse.

Try to recognize that new habits sparked by LS are fragile while over- and under-controlling habits are well established. Be kind to yourself. Walk in the shoes of others when old behaviors snapback. Relapse happens! Simultaneously and mutually shaping direction with everybody is a new set of behaviors! Mastery comes from experience--success + falling off the horse.

Many thanks to my co-author and frequent co-facilitator Henri Lipmanowicz. He has helped me sense when I am falling off the horse. As we developed the LS repertoire, honest and direct coaching made all the difference. To quickly develop your skills, we recommend side-coaching and co-facilitating with one or more partners.

Many thanks to my co-author and frequent co-facilitator Henri Lipmanowicz. He has helped me sense when I am falling off the horse. As we developed the LS repertoire, honest and direct coaching made all the difference. To quickly develop your skills, we recommend side-coaching and co-facilitating with one or more partners.